I recently returned from a

two-week vacation in Europe and Great Britain, leaving my daughter behind in

London for a semester abroad. While there, I had the chance to tour Buckingham

Palace, parts of which are open to the public a few weeks each summer while the

Queen is at Balmoral Castle in Scotland. The state rooms of Buckingham Palace

are fittingly ornate and impressive. I particularly enjoyed walking up the

Grand Staircase to the Ballroom, then into the State Dining Room, where Queen Elizabeth

II is said to personally supervise the details of the place-settings and menu

for each occasion. I felt an undeniable sense of history touring the Palace

during Queen’s Diamond Jubilee year (that’s an amazing 60 years on the throne).

|

| Buckingham Palace (author's photo) |

As part of my Royal Day Out ticket, I also got to tour The Queen’s Gallery, which currently is featuring an

exhibit on Leonardo da Vinci: Anatomist.

And it was there that I received an unexpected, yet very powerful, lesson that

I think relates directly to all of us engaged in tracing our family history.

Before my visit, I didn’t

know that da Vinci, painter of The Last

Supper and Mona Lisa, also studied

anatomy. He made copious notes and fabulously detailed drawings of animal and

human anatomy in the late 1400’s and early 1500’s, keeping them in various

notebooks over the years. By the time he died in 1519, he had made discoveries

and drawn sketches that could have transformed the study of anatomy for

generations to come—if only other scientists had known about it.

But therein lies the rub. You

see, da Vinci never published his ground-breaking work. It remained in loose,

uncollected form upon his death. Even worse, da Vinci wrote his notes using

“mirror writing”—a left-to-right hand style that is extremely difficult to

decipher. Odd notebooks full of strange drawings and unreadable script that

fellow artists and scientists didn’t even realize existed? Sad but true. Da Vinci’s

work disappeared into oblivion. The sketches and notes were eventually

collected into an album and acquired by King Charles II, but they were not

interpreted and their significance recognized until the early 1900’s—roughly 400

years after they were first written. By then, other scientists had made even

greater strides in anatomical studies, and da Vinci’s discoveries had lost

their impact.

|

| Da Vinci's anatomical study of the arm |

|

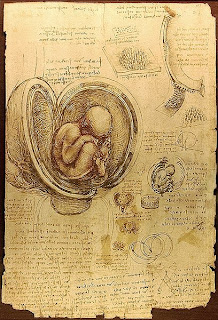

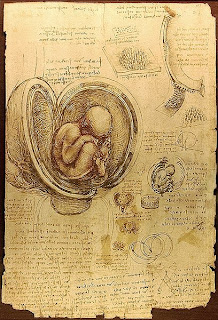

| Da Vinci's drawing of a fetus in the womb |

So what does all this have to

do with family history? In the end, I think it comes down to two words: publish and preserve.

Now I’m the first to admit I

get caught up with the thrill of the hunt. It’s hard to take time out to write my

thoughts and conclusions up when it seems like more ancestors are waiting to be

discovered around every corner. If only I branch out more widely, or reach back

another generation, or break through that elusive brick wall—then I’ll write it

up, I tell myself. It’s not finished yet, and besides, there’s always tomorrow.

But the sad truth is, there’s

not always tomorrow. The recent death of John Humphrey, one of the world’s

foremost genealogists and a wonderfully generous instructor and author, has

driven home that point. Our time here is not unlimited. And if we want our work

to survive us and be beneficial to those who follow, we need to make sure it’s preserved

in useable, accessible form.

The lessons I hope to learn

from da Vinci are:

1. Write in a format that will be

universally readable and understandable for ages to come.

The fact that others couldn’t

read what da Vinci had written was a big part of the problem. How do we make

sure future generations can read our findings? Personally, I think this means we

need to produce material in print rather than rely on computer files. Two

hundred years from now, I’m pretty certain someone will be able to pick up a piece

of paper written in English and read it. I’m not so sure that they will be able to access a DVD, flash drive, or GEDCOM file. And the “cloud” is still

brand new territory. Technological changes are hard to predict, and today's Word file might be mumbo-jumbo tomorrow. Saving things electronically for current use is fine, but

for the long haul, go with the hard copy.

2. Compile your findings into

some organized, cohesive form—a report, article, book, lineage application, chart,

or anthology.

Da Vinci’s lesson here is

straightforward: don’t leave your hard-won research languishing in a stack of

files or notebooks that no one else will make the effort to compile.

Realistically, will your descendents, or even your favorite genealogical

society, be willing to sift through piles of documents or layers of computer

files? And will they know the conclusions you intended to draw? I don’t see

anyone in my family raising a hand for that job. Along with this comes the

responsibility of letting those who read your work know where you got the

information. That doesn’t mean your source citations have to be perfect, as long as they contain enough detail for others to find and

evaluate what you looked at.

3. Share your information with

others by publishing or distributing it.

While publishing a family

history book may be the ultimate goal for many of us, it can also be

intimidating. But publishing doesn’t have to be a huge, one-time proposition. If

you have a blog or family history website, you can publish some findings there.

You could also write an article for your local or state genealogical society

publication. Perhaps you could send copies of a report you write for yourself

to others researching the family. There’s no right or wrong way to get the word

out. Even the simple step of making multiple copies of a family summary and

giving them to a number of people (say, all of your siblings and first cousins)

is valuable. I inherited significant information on two family lines that way. Online

family trees and wikis make it easy to collaborate with other researchers, as

long as caution is used when merging material. And that book you’ve always

wanted to write someday? Maybe a series of mini-books would be a more

approachable goal.

I realize that this is easy

advice to give, but tougher to follow. If I intend to take it, I’ll need to

make compiling and writing up my research more of a priority. But walking

through that elegant gallery admiring what should have been ground-breaking

work, only to discover that it completely lost its impact because it was never

communicated effectively, was a powerful lesson. And it’s one I think has real

significance for all family historians. Who better to learn it from than a

master, and what better place than a royal palace?

--Shelley

(Images of pages from da

Vinci’s notebooks, illustrating his mirror writing, are from Wikipedia Commons

and are in the public domain in the U.S. The photo of the embryo studies page, taken

by Luc Viatour, www.lucnix.be, is considered

one of the finest images in Wikipedia Commons.)

Copyright

2012, Shelley Bishop